Regional Ballot Initiatives – A Flawed Approach to Transportation Investment

July 29, 2020

Regional ballot initiatives may seem like an appealing concept: allow communities to pick their projects, vote on a funding source, and improve their transportation. However, the consequences of enabling regional ballot initiatives are more far-reaching because they would exacerbate local disparities and could result in regressive tax increases.

For a regional ballot initiative, one or more municipalities includes a question on their ballot asking voters to increase a local tax specifically to fund transportation investments. The initiative may note exactly which projects the investments will be used for, but that is not required. Communities may opt to decide after the vote how to spend the additional revenue, so long as it is dedicated to transportation activities. In the Senate’s recent legislation, ballots can be used to raise local sales, property, motor vehicle, or room occupancy taxes.

Advocates of regional ballot initiatives suggest that they will appeal to communities of all income levels because those communities will benefit directly from the tax increase. However, even when a municipality derives full and direct benefits from a tax increase, as they do with property tax overrides, communities with lower incomes still do not adopt the tax increase. The state’s Division of Local Services (DLS) tracks data on property tax overrides and it shows that in those municipalities where residents have lower incomes, voters are simply less likely to adopt an optional additional tax.

The contrasts between which communities adopt property tax overrides is stark, and the resulting disparity in resources is striking. Since fiscal year 2000, of the municipalities with the 10 lowest per capita incomes in the state only North Adams has attempted a property tax override and that failed. On the other hand, the 10 municipalities with the highest per capita incomes in Massachusetts have all adopted multiple overrides during the same time period, totaling nearly $70 million in additional revenue.

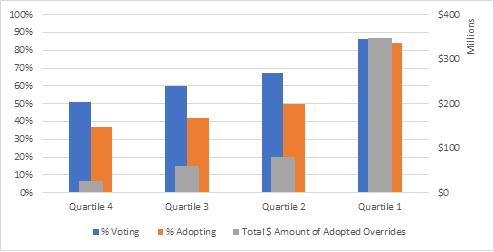

Critically, those communities with lower incomes that did adopt overrides generated significantly less revenue. The 175 municipalities with a per capita income below the state median have approved just $89.5 million in overrides since fiscal year 2000. This contrasts sharply with municipalities above the state median for per capita income: these 175 cities and towns adopted more than $425 million in overrides during the same time – more than four times their lower income counterparts.1 This disparity is the result of both more override approvals and approvals in greater amounts. Figure 1 shows the results on override votes since 2000 by income quartile.

Figure 1: Property Tax Overrides and Approvals

Municipalities by Per Capita Income Quartile, FY 2000 – FY 2020

There is a similar trend with adoption of the Community Preservation Act (CPA). Of the 177 municipalities that have adopted the CPA, the majority are communities with per capita incomes above the state median. Only one-third of the cities and towns that have adopted the CPA have per capita incomes below the state median, despite the option to implement an exemption from the surcharge for low-income property owners.

In addition to the disparity in resources that would arise, regional ballot initiatives would in many cases require a community to adopt a regressive tax. The Senate legislation allows for a room occupancy option, which would not be regressive for residents, but that is not a significant revenue source for many Massachusetts municipalities. For example, New Bedford estimated it would derive less than $300,000 from the room occupancy tax in fiscal year 2020.

Therefore, in many cases regional ballot initiatives would rely on either the sales or property tax to generate revenue for transportation. The state’s Tax Fairness Commission showed in its 2014 report that sales and property taxes are the state’s most regressive. According to data in that report, households in the two lowest income quintiles dedicate the largest shares of their income to paying sales and property taxes.

Conceptually regional ballot initiatives seem like a sensible way to allow local governments to improve their local transportation. However, in Massachusetts we have a long history of allowing municipalities to generate local revenue to fund additional investments and the result is a significant disparity in resources across communities. Massachusetts needs a bold, comprehensive plan for statewide transportation rather than relying on the hope that cities and towns will tax themselves.